Recently, the world of battery-operated music gear welcomed a groundbreaking addition in the form of the Woovebox. Touted as a micro-music workstation, this palm-sized marvel combines the functionality of a synthesizer, sampler, sequencer, and drum machine all in one compact package. As part of my mission to share news and updates about battery-operated music machines, I also believed it would be a fantastic idea to conduct interviews with the minds behind these innovative devices on ‘Battery Op.’ The Woovebox, with its exciting features, seemed like the perfect way to kick off this series.

I was fortunate enough to secure some valuable time from the developer, Ivo, and conduct this inaugural interview, despite the bustling schedule over at Pocket Animal Audio. I truly appreciate his time and insights and I hope you all find this as inspiring as I do.

As an introduction, can you tell us about your background in hardware engineering and signal processing?

I’ve been doing audio signal processing on and off for fun for many years (for some game engines as well as some VSTs for personal use), but have spent most of my time on astronomical signal processing.

I maintain a program called StarTools, which is like Photoshop but specifically for astrophotographers. Its goal is to provide astrophotographers the tools to make images that are as accurate and true-to-life as possible. Astrophotography is part art, part science – it’s complex subject matter and it’s easy to create artefacts or mistakes that compromise the fidelity of your image. StarTools, however, makes it very easy to create high fidelity images with a very simple interface and a very simple workflow.

I’m also involved in a startup that makes content management simple, provides an easy workflow and re-uses that content automatically across multiple platforms.

You might start to see a theme developing here. Making complex tasks easier, more streamlined and more efficient. Doing more with less, through being smarter with inputs, workflows or UI real-estate is definitely my thing. I love efficiently engineered solutions.

Though I had been tinkering with electronics for a long time since I was a kid, the more “proper” hardware engineering is something I only picked up relatively recently (and I still very much feel like an impostor). It started off repairing graphics cards and motherboards, just to learn something new. It required me to better understand schematics, specs etc. of different components and how they function (or – sometimes quite spectacularly – stop functioning…), plus it really helped me develop my soldering skills. The latter really came in handy while prototyping the Woovebox which uses a lot of grain-of-sand-sized components on its PCB.

You’ve mentioned the Woovebox is your “old late 90s/early 00s studio condensed into a pocketable device”. Are there any specific machines from that studio that inspired this one?

The Woovebox really is an amalgamation of the sounds of the gear I owned at the time (as well as gear I wished I owned at the time). But it’s not just the sound, it’s also their unique engineering philosophies, qualities and “reason for being”.

There was a fair bit of early digital gear in that studio. One of the synths was a Kawai K1m (desktop module version of the 1988 K1). In terms of its sound engine, it’s a master class in “doing-more-with-less” engineering to meet a certain budget. The K1 has this airy, digital, yet organic sound of its own, and was still 8 part multi-timbral capable with deep sound design capabilities. Yet its 8-bit waveforms all fit on a 512KB ROM. And that even included percussion.

There was also an AKAI S950 sampler with that lovely crunchy 12-bit sound. Gear from that era actually varied the sample rate it played back at depending on the pitch you need, which gear these days just can’t do. There was no interpolation or up/down sampling to “fit” a fixed frequency engine (e.g 44.1kHz, 48kHz, 96kHz, etc.) as is commonplace now. Just like, say a Commodore Amiga from the same era, each channel/voice had its own DAC that played back digital audio at a different rate, the output of which was summed in the analog domain. If you like that sort of sound, it’s very hard to replicate that same sound in a modern engine or DAW, and it doesn’t help that many people misunderstand lo-fi to begin with. It is so much more than applying a bit crusher VST and be done with it. For the Woovebox, even though its DAC is fixed rate, I wanted to at least be able to do lo-fi properly in terms of the signal path (e.g. pre-filter). Engineers fought tooth and nail to hide or ameliorate digital artefacts; much of the charm of the instruments from that era comes from that unique combination of having multiple DACs, low sample rates, low bit depths, and the analog domain tricks/filters that were employed to smoothen/hide the digital artefacts.

The gear I wished I owned at the time was a JP8000/8080. The JP8000/8080’s Super Saw – as simple as the concept is – was eye/ear-opening. Sonically, there is so much going on in that wall of sound due to the crazy amount of harmonic content. But from a signal synthesis point of view, interestingly enough the same principle is used in analog gear to synthesize some types of percussion. For example the 808 hi-hat uses a bunch of detuned square waves (instead of saw waves) as the initial oscillator. This provides similar rich harmonic content that is then shaped with further circuitry (filters etc.). If you inspect some of the percussion patches on the Woovebox, you will find a number of them (such as the hi-hat or synthesized cymbals) rely on the super saw oscillator to synthesize their percussion in a similar manner.

Which leads us to drum machines like the 808 and 909 that everyone wished they owned. Even in the late 90s those machines were insanely expensive, so back then I did what everyone else did and relied on samples. On the Woovebox however, I ended up pushing the synthesizer’s capabilities enough that I was able to actually synthesize many of their distinct sounds.

And then there were a bunch of rompler-ish synths and sound cards that all were based around the Yamaha XG soundset/standard (CS1x, CS6r, SW1000XG, SW60XG, QY70, EX5r – I was a Yamaha fanboy). They provided decent bread-and-butter sounds that sat well in a mix, but were ultimately not very inspiring nor rewarding to tweak (EX5/EX5r is still a beast though).

So how to capture all those sounds when you embark on creating a whole new device?

The initial idea for the Woovebox was to create something entirely sample-based; not only is it an easy way to lock down to those timbres/sounds fast, it is also the most DSP resource-efficient way of going about making music on a low-powered device.

But was that really the best bang-for-buck? Samples are rather inflexible and always sound the same. It’s really just offloading the sound design to someone/something else. I got started producing music using the early trackers, and that had always been my biggest gripe; I was reliant on samples for everything. Full control over sound design/synthesis is IMO still often an underdeveloped area on many grooveboxes, with most relying on a “tweak-a-preset” paradigm or employing dumbed-down/specialized engines/sandboxes.

Plus, mixing a bunch of sample tracks is – from an engineering point of view – not really a challenge, nor very flexible, nor very sophisticated. Synthesizing something from scratch on the other hand is more exciting; you are master of your own destiny, your own sound. Of course, if the synthesizer sucks or is limited, then that spoils that whole idea of boundless freedom. So I decided I was going to “go hard or go home”. I ditched the samples/rompler idea and designed a synthesis architecture that could provide the essence of all the classic sounds from scratch; as if I would truly have all these devices in my pocket, and not just some recordings of their sounds. And if I really needed recordings of sounds, I could always use the built-in sampler.

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve experienced—so far—when developing the Woovebox? Were there any pleasant surprises?

I knew what I was in for, and all challenges were 100% calculated. The biggest challenge actually had nothing to do with the Woovebox itself. I got somewhat bitten in the backside by the abysmal state of Bluetooth stacks and drivers supplied by Apple and Microsoft in their latest operating systems. It has actually gone down hill over the time I developed the Woovebox. MIDI over BLE has been around since 2015, yet Windows still lacks native drivers. Apple has had native drivers for a while, but in the latest versions of macOS on Intel hardware, the MIDI over BLE connections drop packets like they’re hot (Apple Silicon is 100% stable though). This causes firmware updates and samples transfers to fail randomly for some users, which just sucks. It’s not a nice experience. Dropped packets can happen for any number of reasons, but having the OS “betray” you like that from the get-go is a bad foundation to build a stable connection on. Of course, you can spring for a dedicated MIDI over BLE module like the WIDI Bud Pro, but that’s a (small-ish) extra expense. Over time, I can route around this issue with extra packet-drop detection measures, but it just shouldn’t be that way.

A pleasant surprise, however, was just how far I could push the chip through finding architecture-specific optimizations, cycle counting, scrounging for memory, etc. Working like this is a double-edged sword; you can get amazing performance out of something very small that sips battery power as a result, but you can forget about dropping in generic open-source libraries or code. It would be just way too slow and inefficient. Or vice versa; the code is not terribly suitable for easy porting, understanding or collaboration, and has design decisions in there that would be non-nonsensical on other platforms or architectures.

Can you elaborate on any user-friendly features built into the Woovebox that encourage experimentation and personalization? Are there any ‘hidden gems’ that users might discover when they dig deeper into the device?

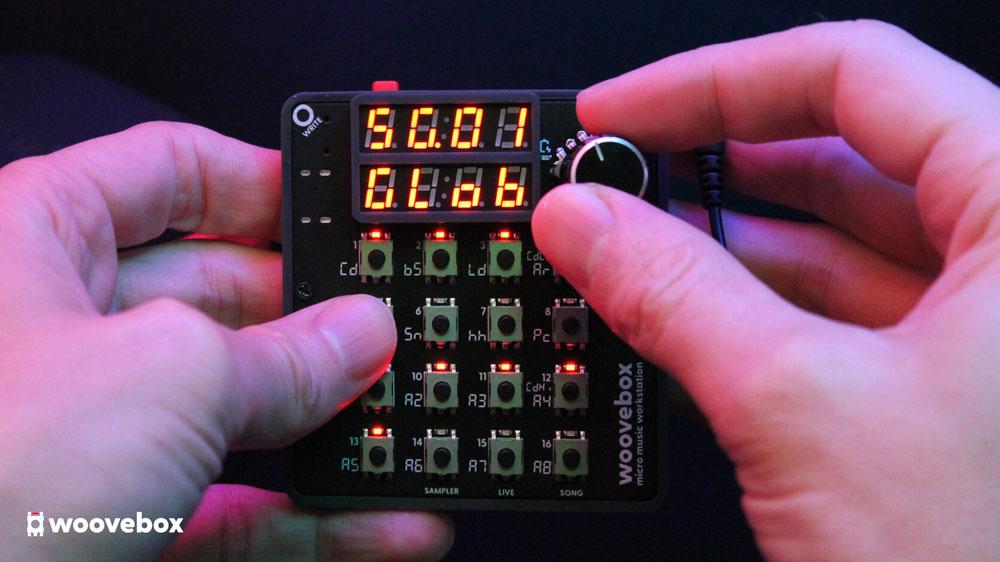

In the days right after announcing the Woovebox, there were one or two videos where a content creator dismissed – without having ever held one – the Woovebox as an “obviously” unusable toy or curiosity. It cannot possibly be easy to use or creatively useful. Not at that size, not with so few buttons/knobs, not with such a low-tech screen. Fortunately, these days comments like that get corrected quite quickly in the comment section by actual Woovebox users.

Indeed, nothing could be further from the truth; everything you need for a fast workflow that inspires is there. No more, no less. And everything is accessible quicker than many other grooveboxes; there is almost 0 menu diving and you barely need the screen. As one YouTube reviewer remarked; “Once you grasped the general idea, you can operate it blindfolded.”. The funny thing is, that it’s not so much the workflow that people struggle to get their head around, it’s more the fact that a fast, fun, and intuitive workflow is even possible with what is presented.

Nothing makes me more more happy than seeing a shadow of a head that belongs to the hands-with-a-voice (you know the video format), bobbing up and down as they discuss, demo or review the Woovebox on YouTube. Because that’s 100% what I was going for; going from 0-to-head-bobbing to a new track in the shortest amount of time. It’s so ridiculously quick and easy to get a cool beat going, and to then create a full song out of that in Song mode. Song mode is the fastest way to break out of the 1-bar loop jail that so many people (myself included) can find themselves in sometimes.

The entire UI and workflow was built around getting you to that head-bobbing-to-your-own-track stage as fast as possible. It’s immediately rewarding, and it encourages you to keep exploring and to keep going, building. The chord following mechanic – where tracks can adapt themselves to the playing chord, scale and key automatically – is definitely a big factor in this. It’s super quick to make something that sounds intentional and refined (even if you just used the random note generator), particularly if you use polymeters and conditionals. That said, you can of course use the Woovebox as a “dumb” groovebox as well, where every note will sound exactly as you programmed it. But if you like happy accidents or “intuited” happy accidents, the Woovebox will put a smile on your face 99% of the time.

As for hidden gems, there’s a fair bit of that! 🙂 As many users have discovered by now, the device is very deep. The quickest way to make the Woovebox your own is definitely sound design. For example, some fun things for people to stumble on, for example, are pitch quantization of the pitch LFOs (for textured/arpeggio runs or fake chiptune-like chords) and the more esoteric synth algorithms. With regards to the latter, there are some unique synthesizer algorithms in the Woovebox that I have never seen implemented in a commercial synth (like exclusive OR synthesis or its FM derivative). That’s because some are pretty obscure or because some are completely home-grown. Other things to discover are Song mode fragment retriggering/automation (stutters, fade-ins, filter sweeps, pitch effects, etc.), polymeters (so much fun!) and the 100+ step conditionals/effects. Dirtying up sounds or samples can also be lots of fun and can quickly yield something unique with loads of character and presence. The Woovebox is also one of the few Grooveboxes that allows for dynamics per track, so you can actually even get into the esoterica of transient shaping if you want!

Users often appreciate the ability to personalize their gear. Could you share any insights into the ease of user-customization for the Woovebox? Are there plans to provide resources like 3D printing files for creating custom cases or suggestions for modifying the device’s interface?

Not as of yet. The trouble with the Woovebox is that it is very small; everything is packed with tight tolerances. Every little space that is free, is free for a reason (whether for ergonomic purposes, wireless radio purposes, or connector space purposes, etc.). There is just very little “frivolous” space to attach things to, to thicken things, support things, hang things off of, etc. If you’re not careful, it’s easy to damage the device just by opening it up, putting it back together or putting to much lateral stresses on its ports (e.g. hanging heavy adapters or whole speakers off it).

That said, I’ve seen some super creative 3D-printed solutions on the Woovebox subreddit for attaching specific things or shading the screen, etc.

Outside of the Woovebox, what are some of your favorite portable synthesizers/drum machines/groove boxes? Are there any you think are a perfect companion?

I owned a QY-70 back in the day, but never truly gelled with it. After being exclusively software for a while, it was the Teenage Engineering PO-33 that rekindled my love for hardware. I bought it on a whim for a long road trip. I loved it so much that only a few months later I decided to get an OP-Z. They’re such great devices. They inspired creativity I hadn’t felt for a long time. Love or hate TE, but the POs in particular are engineering masterpieces on different accounts; the devs should be very proud of what they built – they’re still relevant today. The OP-Z too is an excellently engineered device. There is a bit of controversy about the switchgear and housing, but there are so many things about it that are clever, special and innovative about it (including the housing material, the encoders, the lack of a screen, etc). A lot of things about it were daring, even if maybe – depending on where you stand – they didn’t get it 100% spot-on. If I were Wooveboxless, I’d pick an OP-Z any day.

In terms of the perfect companion for the Woovebox, this answer is going to be weird; 1. any line-level sound source playing a drone chord/sound or 2. the oldest, crappiest 80s/90s kids keyboard you can find that has MIDI IN.

The reason for this strange answer, is that the Woovebox can incorporate up to two sources into its internal sound engine, which you can then treat as oscillators for further sound mangling. So, for example, you can incorporate a guitar drone chord that gets rhythmically gated by the Woovebox in your song. Or you can make your old childhood keyboard sound like a modern monster synth by triggering it from your Woovebox, while your Woovebox applies a filter envelope, distortion and stereo chorus, etc.

Battery-operated and portable music gear definitely inspires us. What is it about portable gear that inspired you to make the Woovebox?

Portable gear gets you away from a specific place (duh Ivo!). What I mean by that, is that sometimes the most logical place to be (e.g. where you have your studio) is not always necessarily the best place to be. I love being able to sit in bed or on my couch with a cat on my lap. Or on a mountain with an inspiring view in front of me. Music is a creative process; mind/feel first, technology later. Sometimes locality can make all the difference in what comes out, or if something comes out in the first place. A lot of people, including myself, want to get away from their laptop and phone screens, and change the setting. That’s the appeal of an ultra-portable groovebox like the Woovebox, or the M8, OP-Z, etc.

Also, limiting yourself to one device that gives you just enough freedom (but not too much!) can also really help the creative process. It pushes you to do more with less and pushes you to question the elements in your compositions. Venus Theory recently did a great YouTube video about embracing minimalism in your workflow. He really hit on some great points (as he tends to do).

Safe to say, I’m super excited to see this new machine grow. Also, your engagement with the community so far, the guides and tutorials ready to go when the Woovebox became available, should have other manufacturers taking note. How has the feedback from the community influenced the development of the Woovebox so far, and do you have plans to continue incorporating user input and suggestions in future updates or products?

Thank you! People trusting you with their support, enthusiasm and hard earned dollars, so that you can deliver this thing that you made; that’s a big responsibility. It’s important to me that people are happy with their Woovebox and feel that their trust and support was justified. I’m so happy that that seems to be the case. While I obviously cannot accommodate every request (most often for technical reasons), feedback has already been very influential; a number of suggestions and fixes have already been released based exactly on that user feedback.

The specifications for the synthesizer, sequencer, and sampler are impressive. Were there any features—hardware or DSP-wise—that you wanted to add to the Woovebox but were unable to?

It sort of worked out the opposite! My MVP (minimum viable product) was going to be the equivalent of a Roland W30 workstation; it had that little bit of everything. Humble – to today’s standards – but a totally viable music workstation nonetheless. It also was one of my earliest memories of seeing a proper work station in real life. Plus, I figured that if it was good enough for Liam Howlett (The Prodigy), then it was good enough for me!

The Woovebox I launched with, however, is far more capable than that machine. I sort of kept going as I found more memory and DSP cycles to save and re-allocate. For example, I really did not expect I would get to the stage where I would find enough DSP cycles to add things like compression. But here we are! The only thing I would have liked to have added, would have been some basic EQ per voice. Maybe I will find enough cycles some day, but it’s going to be stretch – after three years I have really approached the limits of what is possible.

Hardware-wise, a physical MIDI In port (in addition to the virtual BLE MIDI In) would have been nice, but besides space constraints for the connector and associated components, there were some other technical constraints as well.

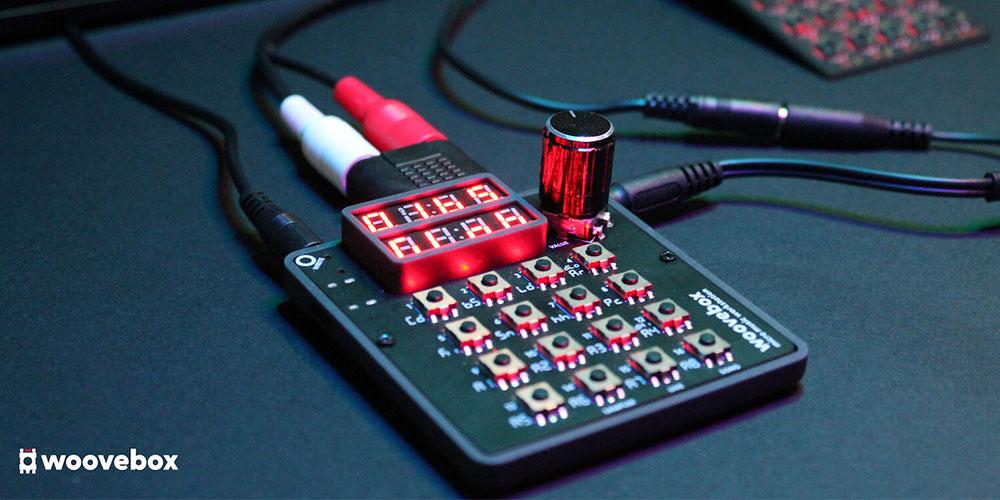

Some people reading this who don’t own a Woovebox yet, may be surprised that I’m not mentioning an OLED screen, which is surely more premium or desirable? Funnily enough, a comparably-sized OLED would have actually been moderately cheaper than the two chunky 7-segment LED modules that I’m using – it’s definitely not a cost saving measure. Most of these reasons for deliberately choosing a 7-segment display, comes down to aforementioned portability, the associated modes of typical use for a portable device, and the simplicity of the workflow.

There are – believe it or not – people that hate bright, tiny OLEDs; because they suck as your eyes get older, and because they hinder your sleep at night when you’re trying to wind down. As mentioned, one of the inspirations for the Woovebox was the OP-Z, which does away with a screen entirely; depending on how a device works you simply don’t need to display much information. The basics are enough, and for many people, ideally a musical device can be operated entirely by audio cues (“blindfolded”); when my day is done, I want to get away from bright touchscreens and use my other senses and other side of my brain.

Same thing goes for the switches; they’re actually just as (typically more!) reliable than the alternative (carbon ink contacts) as used in some other grooveboxes. These switches are actually repairable, serviceable and – if worse comes to worst – replaceable. Everything about the Woovebox is deliberate, utilitarian, calculated, the result of research and the desire to do better. It’s a device made for using, rather than sitting on a shelf being “pretty”; the Woovebox is definitely function over form and challenges learned consumerist “wisdoms” as a result.

Really, if I’d have to design the Woovebox again today with the same design brief, and with what I have learned over the past couple of years, I would 100% design it the exact same way.

Lastly, what’s your vision for the future of the Woovebox? Are there plans for firmware updates, additional accessories, or community support to enhance the user experience that you’re willing to share?

I built the Woovebox as a longer-term development platform, rather than as a one-off/“it-does-what-it-does” product. Even though many hardware aspects are maxed out to their full potential, there are a couple of distinct avenues for expanding on. Without getting too technical or make hard promises just yet, I’m hoping to capitalize on these avenues over the next few months and years, which should give the Woovebox long term relevancy.

To wrap up, I want to thank Ivo (SiliconFields) for an amazing interview. It’s the first one on the site and will no doubt set the tone for future interviews. If you’re just now learning about the Woovebox, or have been on the fence, I hope this interview has you as inspired as I am. I hope those with a Woovebox, or acquiring one soon, will take inspiration from the hidden gems Ivo spoke of and share your creations.

Make sure to check out the full specifications and audio samples of the Woovebox, and while you’re there stop by the Support/Guides/Tutorials page. It has everything you need to get started or just learn more.

We’ll be keeping an eye on this new machine and are very excited to see what the future brings from Pocket Animal Audio.